Phytoliths are a very important identification tool in identifying plants within ancient environments, often even classifying down to the species of the plant.

But firstly, what are phytoliths? As the name phytolith suggests, coming from the Greek phyto- meaning plants and lith– meaning stone, they are tiny (less than 50µm) siliceous particles which plants produce. These phytoliths are commonly found within sediments, and can last hundreds of years as they are made of inorganic substances that do not decay when the other organic parts of the plant decay. Phytoliths can also be extracted from residue left on many different artefacts such as teeth (within the dental calculus), tools (such as rocks, worked lithics, scrapers, flakes, etc.) and pottery.

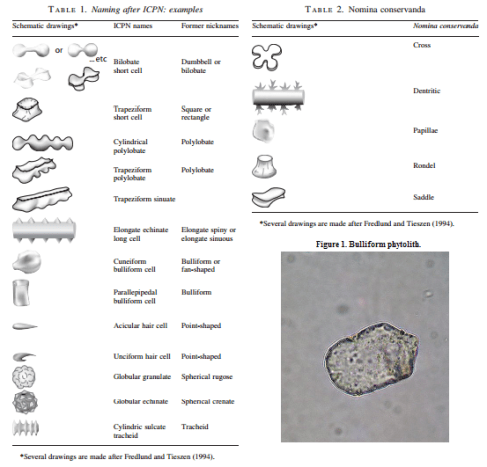

Table 1 & 2: Examples of the descriptors found within the International Code for Phytolith Nomenclature (ICPN), 2005, for use of naming phytoliths.

Figure 1: A bulliform phytolith under a microscope, ©Henri-Georges Nation.

Phytoliths can form numerous striking shapes within the plant cells (figure 1), which gives them a characteristic shape, thus aiding the identification of plants. Due to the vast number of shapes and sizes that phytoliths can come in, researchers compiled the International Code for Phytolith Nomenclature (ICPN), 2005. The ICPN was developed to create a standard protocol which is to be used during the process of naming and describing a new or known phytolith type, as well as a glossary of descriptors to help aid with the naming.

To observe phytoliths, a sediment sample needs to be collected preferably away from any human settlements, as the use of agriculture may have introduced non-native plants to the area. The soil sample is then observed under microscope or even scanning electron microscope (SEM). On the discovery of a phytolith after observation it needs to be named using a maximum of three descriptors, the ICPN (2005) can be used to correctly identify what descriptors should be used.

The first descriptor should be of the shape, either using 3D or 2D descriptor (whichever is more indicative/shows the phytoliths symmetry). The orientation of the phytolith should also be noted. The second descriptor should describe the texture and/or ornamentation, if characteristic or diagnostic and not an artefact of weathering.

The third descriptor should be the anatomical origin, but only when this information is clear and beyond doubt (Madella et al, 2005).

Phytoliths are very important and useful if the sediment they are taken from is hostile to the preservation of fossil pollen, so may be the only evidence available for paleoenvironment or vegetation change.

References:

Balme, J., Paterson, A. 2006. Archaeology in Practice: A Student Guide to Archaeological Analayses. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. Pg 218.

Madella, M., Alexandre, A., Ball, T. 2005. International Code for Phytolith Nomenclature 1.0. Annals of Botany, 96: 253-260. A .pdf of this paper available here.

Renfrew, C., Bahn, P. 1991. Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. Pg 249-53.

Click here to read more Quick Tip posts!