This is the 3rd blog post in this Quick Tips series on estimating the biological sex of human skeletal remains. If you haven’t read the first post on the basics of sexing skeletal remains, click here to start at the beginning or if you skipped the 2nd post focusing on the skull method if sex estimation, click here.

When it comes to sexing skeletal remains by the pelvic elements there are a few trends, as stated in the first blog post in this series, the female pelvic bones, specifically the sacra and ossa coxa are smaller and less robust than their male counterparts.

Figure 1: Side by side size comparison of a male (left) and female (right) pelvis.

Although the female pelvic components are smaller in general, many aspects of the female pelvis are wider than males. The pelvic inlets on a female are relatively wider than those of males, as well as the greater sciatic notches – which is thought to aid childbirth.

Figure 2: Basic labelled diagram of the pelvic anatomy.

There are numerous features of the pelvic bones that are examined to identify the biological sex of an individual, alongside the trends stated about. These features are as follows;

- The ventral arc.

- The subpubic concavity.

- The medial aspect of the ischiopubic ramus.

- The greater sciatic notch.

The first three features listed above, are known as the Phenice method – which was proposed by T. W. Phenice in 1969. His paper, “A Newly Developed Visual Method of Sexing the Os Pubis”, contributed greatly to the method of visual determination of sex, as beforehand the methods were subjective and based largely on the osteologist’s experience. The Phenice method should only be used for fully adult skeletal remains, where it is 96 to 100% accurate.

The ventral arc is a slightly raised ridge of bone that sweeps inferiorly and laterally across the central surface of the pubis. It joins with the medial border of the ischiopubic ramus. The ventral arc is only present in females, although males may have raised ridges in this area, but these do not take the wide, evenly arching appearance of the ventral arc.

Figure 3: The ventral arc is characterised by a slightly raised ridge of bone. Males (left) do not exhibit the ventral arc, where as females (right) do.

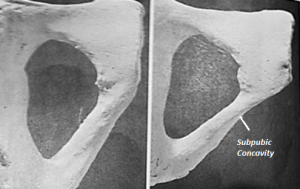

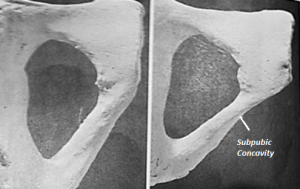

To observe the subpubic concavity, you should turn the pubis so that the convex dorsal surface if facing you. Then you should view the medial edge of the ischiopubic ramus. Females display a subpubic concavity here where the edge of the ramus is concaved, whereas males tend to have straight edges or very slightly concaved.

Figure 4: Females (right) display a subpubic concavity here where the edge of the ramus is concaved, whereas males (left) tend to have straight edges or very slightly concaved.

To observe the medial aspect of the ischiopubic ramus, you should turn the pubis 90° so that the symphyseal surface is directly facing you. View the part of the ramus that is directly inferior to the pubis symphysis. In females, the ramus has a sharp, narrow edge, whereas in males it is flat and blunt.

Figure 5: In females (right), the medial aspect of the ischiopubic ramus has a sharp, narrow edge, whereas in males (left) it is flat and blunt.

As with the five features of the skull used to sex a skeleton in the previous, the greater sciatic notch has also been given a numerical score from 1 to 5 relating to the level of expression. It has been generally found that female os coxae are more likely to exhibit a lower level of expression, whereas male os coxae are more likely to have higher levels of expression.

Figure 6: It has been generally found that female os coxae are more likely to exhibit a lower level of expression, whereas male os coxae are more likely to have higher levels of expression, when it comes to the greater sciatic notch.

To obtain the best results whist examining the os coxae, it should be held in the same orientation as the pictured above. This allows you to match the angle of the greater sciatic to the closest expression that represents it. It should be noted that this method is usually used as a secondary indicator.

References:

Buikstra, J.E., Ubelaker, D.H. 1994. Standards for Data Collection From Human Skeletal Remains. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Archaeological Survey Report Number 44.

Ubelaker, D.H. 1989. Human Skeletal Remains: Excavation, Analysis, Interpretation (2nd Ed.). Washington, DC: Taraxacum.

White, T.D., Folkens, P.A. 2005. The Human Bone Manual. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Pg 392-398.

This is the third post of the Quick Tips series on sex determination of skeletal remains. The next post in this series will focus on the use of DNA to determine biological sex. To read more Quick Tips in the meantime, click here!