Isotopic analysis is widely used within the worlds of archaeology and anthropology. From analysing isotopes we’re able to uncover a wide range of information regarding the past; ranging from palaeoenvironments to palaeodiets, and even using isotopes to reconstruct trade routes of materials.

But first, what are isotopes?

All of the chemical elements consist of atoms which are specific to the element and the mass of an atom is dictated by the number of protons and neutrons it contains. The identity of the chemical element depends on the number of protons found within the atom’s nucleus, but the number of neutrons within the atom can vary. Atoms of the same chemical element (same number of protons), but with different masses, which is from the varying amount of neutrons, are called isotopes.

Within nature, most of the elements consist of a number of isotopes. These isotopes can be found within water, livestock, crops and plants, which can then be used to reconstruct palaeodiets and palaeoenvironments.

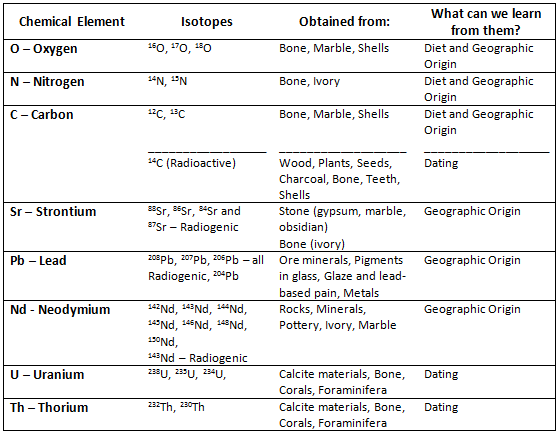

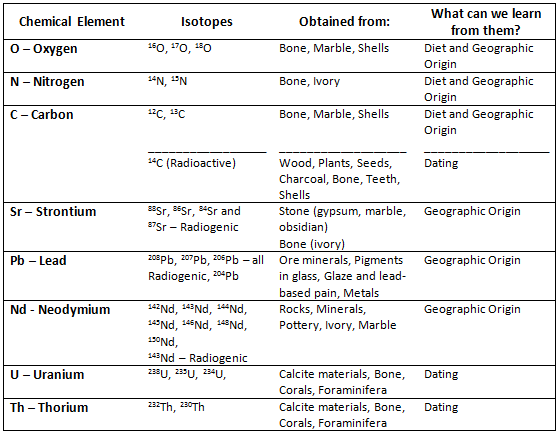

Within nature, most of the elements consist of a number of isotopes. For a great majority of elements these relative proportions of isotopes are fixed, but there are a group of elements which either due to chemical or biochemical processes are of variable isotopic composition. These elements are oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and sulphur. Another group of isotopes that are used for analysis are strontium, lead and neodymium. These are formed by elements which contain stable but radiogenic isotopes, which are formed by radioactive decay of another element. Carbon and nitrogen isotope composition are primarily used to reconstruct diets, and oxygen isotopes are used to determine geographic origin. Strontium and lead isotopes found within teeth and bone can sometimes be used to reconstruct migration patterns in human populations and cultural affinity

A table of the various elemental isotopes that are valuable in archaeological and anthropological research.

But how do isotopes get into skeletal remains?

Carbon isotopes are taken up through the diet of animals during their lifetime and these isotopes are deposited into teeth and bones of humans when they are consumed and digested. By studying animal bones and examining the 12C and 13C isotope ratio, it is possible to determine whether the animals ate predominately 3C or 4C plants. Oxygen isotopes are constantly being taken up and deposited into the body through the water a population drinks. This process ends with the organism’s death, from this point on isotopes no longer accumulate in the body, but do undergo degradation. For best result the researcher would need to know the original levels, or estimation thereof, of isotopes in the organism at the time of its death.

By creating a map of these natural occurring isotopes in different environments, rivers and areas, it is possible to identify where in an area the population lived, sourced their water or where the livestock grazed, by comparing the levels of isotopes that were obtained from skeletal remains to the environmental map. This mapping can also help identify trade routes that once existed and can also identify the migration patterns of populations.

References:

Balme, J., Paterson, A. 2006. Archaeology in Practice: A Student Guide to Archaeological Analayses. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. Pg 218.

Renfrew, C., Bahn, P. 1991. Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. Pg 249-53.

If you’re new to the realm of archaeological, anthropological and forensic sciences (AAFS), or are a student needing sturdy and reliable references, or wondering “what archaeology or anthropology textbooks to buy?” Check out our new ‘Useful Literature’ page!